Background

Chlamydia is the most commonly diagnosed bacterial sexually transmissible infection (STI) in Australia. Partner management is key to reducing transmission and a cornerstone of best practice chlamydia management. While most patients will opt for telling their partner(s) themselves, patient-delivered partner therapy (PDPT) offers an alternative way to inform and treat partners where usual management is inappropriate or unlikely to be undertaken. Guidelines for PDPT vary across Australia. Recent research found that general practitioners (GP)s want practical guidance for using PDPT in appropriate situations.

Objective

The aim of this article is to provide an overview of the process of offering PDPT and note the challenges GPs may face in its provision.

Discussion

PDPT is one option for partner management when sexual partner(s) are unlikely or unable to seek timely care themselves. However, there are challenges to the use of PDPT in general practice. The provision of clear guidelines is an essential step to promote its appropriate use.

Chlamydia is the most commonly diagnosed bacterial sexually transmissible infection (STI) in Australia, with notifications continuing to increase over the past decade, particularly among people aged 15–29 years.1 Repeat infections are common, with an estimated 22.3% of women aged 16–25 years acquiring another chlamydia infection within four months of their initial infection,2 while approximately 11% of men across all ages will acquire a repeat chlamydia infection within four months. (same reference applies).3 In this article we use the term ‘women’ to refer to people with female reproductive organs, and ‘men’ to refer to those with male reproductive organs. However, we acknowledge that not all people with female reproductive organs identify as women, and not all people with male reproductive organs identify as men. Repeat infection significantly increases the risk of chlamydia-related complications in women, including pelvic inflammatory disease (PID).4 Although testing and effective treatment are key to reducing the burden of disease, management of sexual partner(s) and testing for repeat infection are vital to reducing ongoing transmission, preventing repeat infection and progression to adverse sequelae.5

Best practice chlamydia management includes the management of sexual partner(s).6 The current National Sexually Transmissible Infections Strategy (National STI Strategy) highlights partner management as key to reducing STI transmission.7 While local health departments provide advice and resources to help with partner management, it is the diagnosing clinician who is responsible for discussing partner management with index cases and providing support for this process. Most patients will opt for telling their partner(s) themselves, and in these cases providing the index case with a factsheet about chlamydia, and/or an example of how to word a text message to their partners, may be helpful (refer to http://contacttracing.ashm.org.au/contact-tracing-guidance/introduction and www1.racgp.org.au/ajgp/2021/january-february/chlamydia-associated-reproductive-complications-in for examples and links to resources). The use of patient-delivered partner therapy (PDPT) may be appropriate in some cases following discussion with the patient.

PDPT is where the diagnosing clinician provides either an extra prescription or additional medication to the index case for the treatment of their partner(s) without the clinician first seeing the partner(s). PDPT has been shown to reduce repeat infection in the index case compared with partner notification practices without treatment provision.8 PDPT may also reduce the time to treatment for sexual partners; a recent observational study in an Australian sexual health clinic reported that among their participants, most sexual partners took their antibiotics on the same day as the index case.9 Importantly, patients appreciate having the option of PDPT available to them.10

Health authorities in Victoria,11 New South Wales12 and the Northern Territory13 have provided PDPT guidance allowing prescription or supply of azithromycin for partners of patients with uncomplicated chlamydia. While other jurisdictions have not provided any guidance, a recent review of the policy environment for PDPT found that PDPT was potentially allowable under relevant prescribing regulations in most other Australian jurisdictions including Western Australia, South Australia, Australian Capital Territory and Tasmania, where it is neither expressly permitted nor prohibited.14 However, PDPT is not recommended in South Australia15 because of concerns about azithromycin-resistant gonorrhoea. All general practitioners (GPs), regardless of the jurisdiction in which they practice, can access information about PDPT via the Australasian Contact Tracing Guidelines (http://contacttracing.ashm.org.au) and can contact their local health departments for information relevant to their jurisdictions.

The National STI Strategy notes that primary care settings should be supported to engage in best practice chlamydia management, including the integration of PDPT as an option for partner management into routine care.7 Our recent research with Australian GPs found that they offer PDPT when they feel it is beneficial for their patient, even in the absence of health authority guidance.16 Participants also reported they would like practical guidance for providing PDPT.16 In this article, we give an overview of the process of offering PDPT as one option for undertaking partner management for chlamydia, including how to overcome potential challenges in its provision.

Offering PDPT to chlamydia-positive patients for their sexual partner(s)

For heterosexual patients with uncomplicated anogenital or oropharyngeal chlamydia whose partner(s) are unable or unlikely to seek timely treatment themselves, or when the index patient has repeat infection, the diagnosing clinician may consider offering PDPT. A single dose of azithromycin 1 g orally is used for PDPT. In deciding whether to offer PDPT, the GP may also consider the individual benefits for the patient, including a dramatically reduced risk of repeat chlamydia infection. PDPT is not suitable for patients:

- whose partners are pregnant

- with multiple STIs

- whose partner(s) may be at increased risk of human immunodeficiency virus or other STIs (eg men who have sex with men)

- at risk of partner violence17

- for whom the clinician may have concerns about their mental health

- whose partners are allergic to the therapy.

The case study in Box 1 presents a likely scenario in which PDPT could be useful.

| Box 1. A case study for offering PDPT to an index case |

A woman aged 25 years presents to your general practice for her first cervical screening test. You note she was diagnosed with chlamydia eight months ago and did not return for repeat testing as recommended three months after treatment. You explain the importance of retesting and offer another chlamydia test, to which your patient agrees.

The test is positive, and the patient is recalled for treatment and to discuss partner notification.

Your patient reports one male partner in the past 18 months, with whom she lives. You ask your patient if her partner is likely to attend the clinic for treatment. She explains that while she had asked him to get partner treatment when she was first diagnosed, he did not manage to see a doctor and she thinks it is unlikely this time too. You therefore offer an extra prescription of antibiotics for her partner, which she accepts. You print a PDPT information sheet for the patient and her partner and with your patient’s consent, you make an entry in her medical record that she has accepted the offer of antibiotics for her partner and record her partner’s name and address. Your patient is not sure about her partner’s allergy status but agrees to check within him and provide the information sheet with the antibiotics. You then generate a prescription for your patient in her medical record and use a letter template (that your clinic has set up in your electronic medical record to facilitate use of PDPT; refer to Appendix 1 for sample template) to write a prescription for azithromycin 1 g orally for your patient’s partner (private prescription). You advise your patient that she and her partner should take the antibiotics straight away and abstain from sex for seven days after taking the antibiotics, and you place her on recall for follow-up. You also suggest that it would be a good idea for her partner to have a sexual health check-up.19 |

| PDPT, patient-delivered partner therapy |

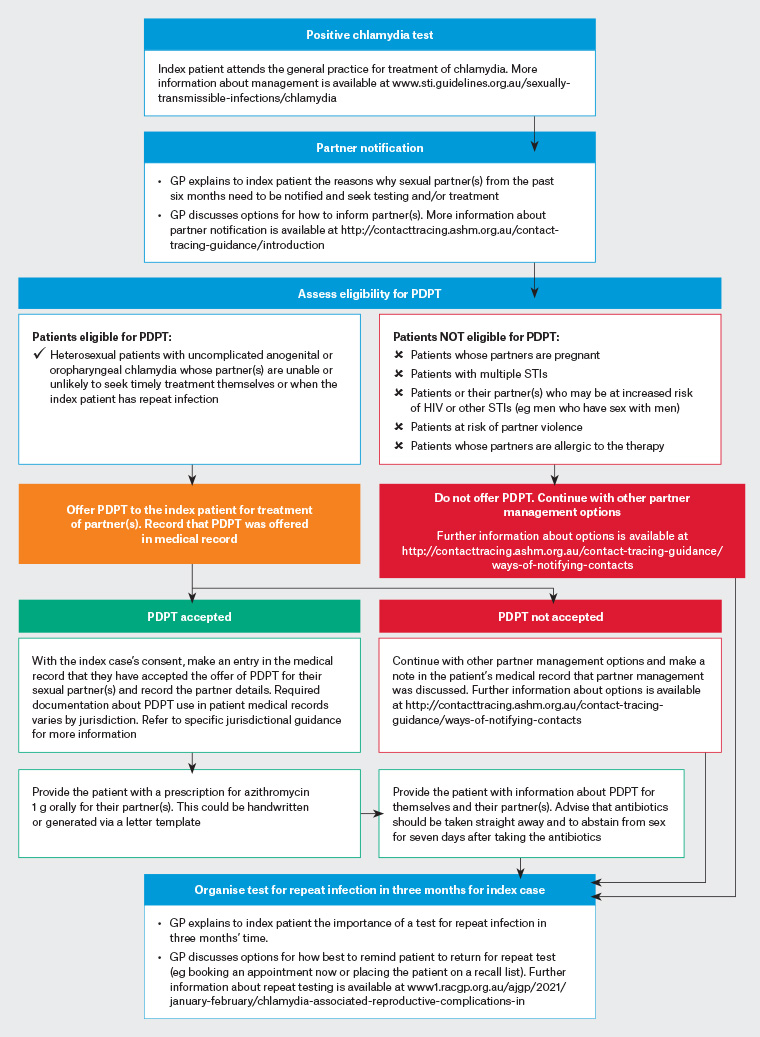

Where guidance has been provided, the required documentation about PDPT use in patient medical records varies by jurisdiction. In Victoria, GPs are required to note the partner(s) full name and address, provision of information sheet, method of writing the prescription and any other medical information known about the partner(s) at the time of the consultation.11 In New South Wales, GPs are required to note the partner(s) full name and their home address and/or their mobile number and/or email address in the index case’s record.12 A PDPT autofill in the electronic medical record can be helpful for supporting best practice PDPT documentation (Appendix 2). Partner details can be either captured in the index patient’s progress notes or a subsection of the medical record, depending on local policies, and, in the case of a third-party medical record request, can be redacted as required. The Northern Territory does not include specific instructions regarding what partner details are required to be recorded. Figure 1 provides an overview of the process for offering PDPT to chlamydia-positive patients for their partner(s).

Figure 1. Offering PDPT to chlamydia-positive patients. Adapted from New South Wales, Victorian and Northern Territory guidelines; 11–13 refer to specific jurisdictional guidelines for further advice. Click here to enlarge.

GP, general practitioner; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; PDPT, patient-delivered partner therapy; STI, sexually transmissible infection

Challenges to using PDPT in general practice

While PDPT has been shown to facilitate timely treatment of sexual partners and prevention of repeat chlamydia infection,8 Australian GPs have identified some challenges with using PDPT.14,16,18 These challenges, and suggestions for how they can be overcome, include the following.

- Lack of opportunity to provide safer sex education or to test the partner for STIs

- Recording partner(s) details in the index case’s medical record

- Documenting information provided by a patient in their medical record complies with standard history-taking practice and is supported by jurisdictional guidelines in some states and territories.

- Generating a prescription for a patient not seen

- Extending the duty of care to partner(s) supports index patient care and community chlamydia prevention efforts.

- True allergy to azithromycin is rare and adverse reactions are noted clearly on PDPT partner factsheets and consumer medicine information.

- Billing for a patient not seen

- Partner consultations via telehealth are an option for additional billing for STI-related consultations.

To advance partner management and facilitate broader integration of PDPT into routine care for chlamydia, development of clinical and jurisdictional-specific guidelines for all Australian states and territories regarding the use of PDPT in general practice is a critical next step.

Conclusion

Partner management is key to reducing STI transmission and is a cornerstone of best practice chlamydia management. PDPT offers an alternative way to inform and treat partners where usual management is inappropriate or unlikely to be undertaken. This article provides guidance for clinicians who want to provide PDPT safely and in accordance with their relevant jurisdictional guidelines, acknowledging that not every clinician will want to nor need to provide PDPT. The development of clinical and jurisdictional-specific guidelines for all Australian states and territories regarding how PDPT can be used in general practice is a critical next step in helping GPs integrate PDPT into routine care as another partner management option. This must be done in consultation with the relevant professional bodies (The Royal Australian College of General Practitioners and the Royal Australasian College of Physicians Chapter of Sexual Health Medicine).

Key points

- Partner management is a cornerstone of best practice chlamydia care.

- The diagnosing clinician is responsible for discussing partner management with index cases.

- While most patients will opt for telling their partner(s) themselves, PDPT is one option for informing and treating partner(s) who are unlikely or unable to seek timely care themselves.

- PDPT has been shown to reduce repeat infection in the index case.

- Health authorities in Victoria, New South Wales and the Northern Territory have provided PDPT guidance allowing prescription or supply of azithromycin for partners of patients with uncomplicated chlamydia.